Home » Resources » UXO City Guides »

UXO City Guide

Home Office Bombing Statistics for Norwich

Record of German Ordnance dropped on the County Borough of Norwich

High Explosive Bombs (All types)

561

Parachute Mines

0

Oil Bombs

2

Phosphorus Bombs

24

Fire Pots

84

Pilotless Aircraft (V-1)

0

Long-range Rocket Bombs (V-2)

0

Weapons Total

671

Area Acreage

7,898

Number of items per 1,000 acres

85.0

Why was Norwich targeted and bombed in WWII

During WWII, Norwich was not a major industrial or manufacturing centre, nor did it have significant military or strategic importance. The city was famed for its medieval architecture, cathedral and historic centre.

During the early months and years of the war, it therefore saw relatively little Luftwaffe attention. Between July 1940 and August 1941, Norwich saw 27 small raids – mainly ‘tip and run’ style incidents made by a lone or small number of aircraft – resulting in the deaths of 81 citizens.

Damage was scattered, with light engineering works, transport infrastructure and surrounding airfields targeted. An example of one of the targets identified by the German Military around this time can be seen in the Luftwaffe reconnaissance map below.

The city would see no night raids at all for the next eight months1. However, this changed on the night of 27th April 1942 when a Norwich suffered a major attack.

The Norwich Baedeker Raids

Norwich’s historic architectural significance would unfortunately cost it dearly in April and May 1942. In March 1942, the RAF bombed the old town of Lübeck in northern Germany. Like Norwich, it had no particular strategic significance, but was chosen as a target because it was easy to reach and offered a chance to test the effectiveness of area bombing and incendiary attacks.

Hitler was reportedly so incensed that he ordered reprisal attacks. Five British cities of historic and cultural significance (allegedly selected from the German Baedeker travel guide) were chosen – including Norwich.

The raid of Monday 27th April lasted for two hours in total. Over 50 tons of explosives were dropped – more than 185 high explosive bombs. 162 people were killed, with 600 injured, and some 84 people were dug out of rubble alive.

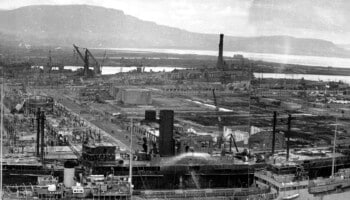

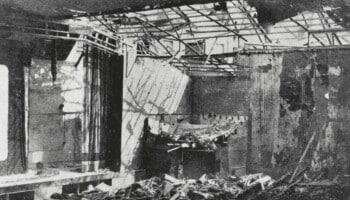

Buildings notably affected included St Augustine’s School, the Norwich Institute for the Blind, the Odeon Cinema in Botolph Street, the Public Assistance building on Bowthorpe Road, and Grapes Hotel at Earlham Road2. The areas and buildings damaged in total across the city were however almost too great to list. Some examples of the level of damage sustained can be seen in the images below.

The city had a night of reprieve before a second shorter but equally devastating raid on Wednesday 29th. As before, flares were dropped to light up the city centre, followed by 112 high explosive bombs. A much higher proportion of incendiary bombs were deployed, and fires raged across previously bombed areas of the city. One of the largest areas affected was around Curls’ department store at Orford Place, St Stephen’s Street, Giles Street, Rampant Horse Street and St Benedict’s Gates.

Norwich city centre was hit again on Friday 1st May 1942. This was another night of fires, with the main shopping centre of Norwich nearly gutted. The raid was mostly repelled by the city’s ground defences, but one aircraft dropped a single container of 700 1kg incendiary bombs, which scattered across Heigham Street, Duke Street, St Andrew Street, and across the back of London Street3.

Additional bombing raids occurred sporadically throughout the rest of the year, right up until 6th November 1943.

The aftermath of the bombing of Norwich

The two Baedeker Raids resulted in the deaths of 229 people – one of the largest air raid casualties in Eastern England. Over 2,000 houses were destroyed, with another 27,000 suffering damage. Few areas of the city were left unaffected4. Below is an extract of a bomb map of Norwich showing the All Saints Green area, held at the Norfolk Record Office. Each pin/pinhole represents a bombing incident.

Unexploded bombs were a serious issue following the raids. The accurate reporting of the location of unexploded bombs helped in evacuation and traffic diversions – and prevented the sending of Bomb Disposal Units on unnecessary journeys. By daybreak following the second main raid, 30 unexploded bombs had been reported to Police Headquarters.

Of the suspected UXBs reported after the Baedeker Raids, 68 were confirmed by Reconnaissance Officers, 21 were assessed to be exploded 50kg and six were discredited. Of the remainder, five later exploded and the rest were removed by the Army Bomb Disposal Squad. The images below show two examples of UXBs being removed from the streets of Norwich.

Home Office Bombing Statistics for Norwich

Details obtained from Home Office bombing statistics, indicates the quantity and type of bombs that fell on the County Borough of Norwich during WWII (excluding incendiary bombs).

A total of 561 recorded bombs fell on Bristol according to official statistics, equating to an average of 85 items of ordnance recorded per 1,000 acres. However, this does not account for any bombs that fell unrecorded and unexploded during the raids of the city. These unidentifiable items are what pose a potential risk to construction projects today.

Can UXO still pose a risk to construction projects in Norwich?

The primary potential risk from UXO in Norwich is from items of German Air-delivered Ordnance which failed to function as designed. Approximately 10% of munitions deployed during WWII failed to detonate, and whilst efforts were made during and after the war to locate and make UXBs safe, not all items were discovered. This is evidenced by the regular, on-going discoveries of UXO during construction-related intrusive ground works across the UK – not just in Norwich.

Occasionally items of British explosive ordnance are also encountered – often associated with WWII defensive measures or Home Guard operations. However, there were few military related facilities in or around the city.

I am about to start a project in Norwich, what should I do?

Developers and ground workers should consider this potential before intrusive works are planned, through either a Preliminary UXO Risk Assessment or Detailed UXO Risk Assessment. This is the first stage in our UXO risk mitigation strategy and should be undertaken as early in a project lifecycle as possible in accordance with CIRIA C681 guidelines.

It is important that where a viable risk is identified, it is effectively and appropriately mitigated to reduce the risk to as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP). However, it is equally important that UXO risk mitigation measures are not implemented when they are not needed.

While there is certainly potential to encounter UXO during construction projects in Norwich, it does not mean that UXO will pose a risk to all projects. Just because a site is located in Norwich does not mean there is automatically a ‘high’ risk of encountering UXO. It really does depend on the specific location of the site being developed.

A well-researched UXO Risk Assessment will take into account location specific factors – was the actual site footprint affected by bombing, what damage was sustained, what was the site used for, how much would it have been accessed, what were the ground conditions present etc.

It should also consider what has happened post-war – how much development has occurred, to what depths have excavations taken place and so on. This will allow an assessment of the likelihood that UXO could have fallen on site, gone unnoticed and potentially still remain in situ.

Sources

1Norwich at War, Joan Banger

2http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Website/raids.htm

3Norwich at War, Joan Banger

4http://www.oldcity.org.uk

Recent UXO discoveries in Norwich

Since the war, many items of UXO have been discovered across multiple cities within the UK, with Norwich no exception. See the news articles below about UXO incidents and discoveries from national and local press in Norwich.

1st Line Defence keep up-to-date with relevant and noteworthy UXO-related news stories reported across the UK, and you can browse through these articles using the buttons below.

Get UXO risk mitigation services from a partner you can trust

UXO City Guides

Got a project in Norwich? Need advice but not sure where to start?

If you need general advice about UXO risk mitigation in Norwich, get in touch.

Contact Us

* indicates required fields