Home »

What is UXO?

Unexploded Ordnance (UXO) is a term used to describe explosive weapons (high-explosive bombs, landmines, projectiles, mortars, grenades, bullets etc.) that did not explode when they were deployed and still pose a risk of detonation. UXO also refers to explosive weapons which were primed, fused or armed but failed to detonate when they were used during an armed conflict – or were left behind, buried or dumped.

UXO in the UK can originate from three principal sources:

- Munitions resulting from wartime activities including German bombing in WWI and WWII, long range shelling and defensive activities.

- Munitions deposited as a result of military training and exercises.

- Munitions lost, burnt, buried or otherwise discarded either deliberately, accidentally or ineffectively – often on land utilised historically by the military.

When an item of UXO is discovered it should be safely disposed, this is usually carried-out via a controlled explosion or moved to a location where it can be safely destroyed.

What are the hidden dangers of encountering UXO?

The biggest danger of unexpectedly encountering UXO is the accidental detonation of high explosive fill, which can result in injury/death and blast damage. Various other risks exist depending on the type of UXO encountered.

For example, some ordnance dating back to WWI can pose a chemical threat. Chemical risks can also be presented by smoke and incendiary filled weapons, and environmental risks such as heavy metal contamination of soil and water should also be considered.

The size or shape of any item of UXO does not necessarily indicate its potential danger. Even small items of ordnance can seriously endanger or kill if handled incorrectly – it is better to be safe and take the correct precautions.

Explosive ordnance can become unstable and sensitive to movement, impact, vibration and temperature changes. If you ever encounter an item which you suspect might be UXO, it is crucial to avoid touching or moving it – and to call the police or a specialist UXO risk mitigation company like 1st Line Defence for assistance.

How many items of UXO are discovered every year?

Every year across the UK, thousands of unexpected discoveries of unexploded ordnance (UXO) are made.

From items washing up on beaches to munitions uncovered in gardens, sheds and attics, UXO continues to surface in surprising places. Discoveries are frequently made by members of the public – including magnet fishers and dog walkers – as well as by construction and infrastructure workers during ground-disturbing activities.

Due to the inherent risks involved, and the disruption these finds can cause, suspected UXO incidents often attract significant attention from local and national media.

At 1st Line Defence, we closely monitor and track notable UXO-related incidents reported across the press. We have created a page which brings together relevant media coverage, allowing you to explore recent discoveries and trends either via our interactive map or through links to the press articles.

To view UXO-related press articles published in 2026, 2025 & 2024, select one of the buttons below.

What can be done to manage and mitigate UXO risk on construction projects?

The management of UXO risk is critical to avoid possible injury, delays and cost overruns in construction projects across the UK and Internationally.

We offer a wide range of specialist Land UXO Services and Marine UXO Services to help mitigate the risks associated with all types of explosive ordnance – reducing time and costs.

Our specialist UXO Risk Mitigation Services include:

How many different types of UXO were used?

There are many exceptions to the rule, but most commonly in the UK, UXO will generally fall into two categories:

- British / Allied Explosive Ordnance (items fired, lost, dropped, buried, burned or otherwise discarded by British and Allied forces in the UK)

- Air-Delivered Explosive Ordnance (generally German high-explosive, incendiary and anti-personnel bombs)

Military / Allied Ordnance

Grenades>

Image showing a No.5, No.36 and No.69 Grenade

Image showing a No.5, No.36 and No.69 Grenade

A grenade is a short range weapon designed to kill or injure people. It can be hand thrown or fired from a rifle or a grenade launcher. Grenades can contain high explosive or smoke producing pyrotechnic compounds. Some common variants have a classic ‘pineapple’ shape (such as the No. 36 grenade, in service from 1915 until the 1980s).

A modern hand grenade generally consists of an explosive charge, a detonator mechanism, an internal striker to trigger the detonator, and a safety lever secured by a pin. The user pulls the safety pin before throwing, and once thrown the safety lever gets released, allowing the striker to trigger a primer that ignites a fuze, which burns down to the detonator and explodes the main charge.

Mortars>

Image showing a 2-inch Mortar and a 51mm Mortar (Illuminating)

Image showing a 2-inch Mortar and a 51mm Mortar (Illuminating)

A mortar is a generally simple, portable, lightweight, muzzle loaded weapon, consisting of a metal tube on a baseplate which launches mortar rounds in high-arcing ballistic trajectories. The mortar round is normally nose-fused and fitted with its own propelling charge. Its flight is stabilised by the use of a fin.

They are usually tear-drop shaped (though older variants are parallel sided), with a finned ‘spigot tube’ screwed or welded to the rear end of the body which houses the propellant charge. Mortars are either High Explosive or Carrier (i.e. smoke, incendiary, or pyrotechnic).

Projectiles>

Image showing a 25lb Projectile (HE) and a 40mm Bofors Anti-aircraft Projectile

Image showing a 25lb Projectile (HE) and a 40mm Bofors Anti-aircraft Projectile

A projectile (sometimes referred to as a ‘shell’) is propelled by force, normally from a gun, and continues in motion using its kinetic energy. The gun a projectile is fired from usually determines its size. A projectile will often contain a fuzing mechanism and a filling. Projectiles can be high explosive, carrier or Shot (a solid projectile).

Small Arms Ammunition>

Image of various items of Small Arms Ammunition

Image of various items of Small Arms Ammunition

The most common type of ordnance encountered on land used by the military are items of Small Arms Ammunition (SAA). SAA refers to the complete round or cartridge designed to be discharged from varying sized hand-held weapons such as rifles, machine guns and pistols.

SAA can include bullets, cartridge cases and primers/caps.

Rockets>

Rockets were commonly designed to destroy heavily armoured military vehicles (anti-tank weapon). The device contains an explosive head (warhead) that can be accelerated using internal propellants to an intended target. During WWII, anti-aircraft rocket batteries were also utilised in the UK as part of air defence measures.

Landmines>

A landmine is designed to be laid on or just below the ground to be exploded by the proximity or contact of a person or vehicle. During WWII, they fell into two main categories – Anti-Personnel (AP) and Anti-Tank (AT). Landmines were often placed in defensive areas of the UK during WWII to obstruct potential invading adversaries.

Air-delivered Ordnance

High Explosive Bombs>

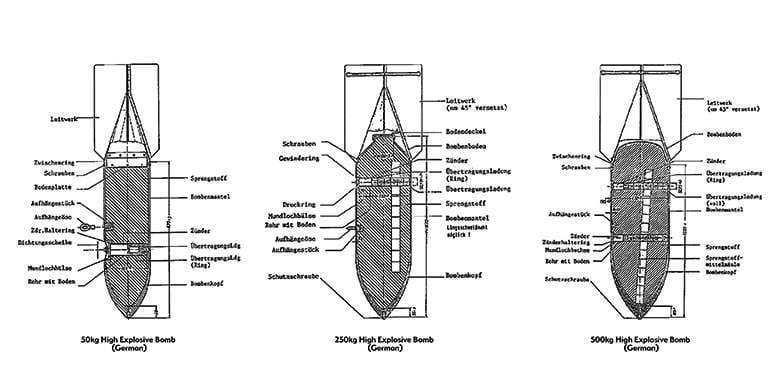

Schematic diagram of a 50kg, 250kg and 500kg High Explosive German Bomb

Schematic diagram of a 50kg, 250kg and 500kg High Explosive German Bomb

A ‘High Explosive’ (HE) material is one that is designed to detonate (as opposed to deflagrating or ‘Low’ explosive). It is characterised by extremely rapid decomposition and development of very high pressure. When such explosive is encased, it effectively becomes a ‘bomb’.

During WWII, conventional high explosive bombs were dropped in their thousands by both German and Allied forces. They had a thick metal casing that would fragment on detonation. The main charge would be triggered by a fuze. In terms of weight of ordnance dropped, HE bombs were the most frequently deployed by the Luftwaffe during the war.

Common variants of high explosive bombs dropped on the UK during WWII were the 50kg, 250kg and 500kg – with a smaller percentage of 1000kg (nicknamed the ‘Hermann’) and 1800kg (the ‘Satan’).

Although efforts were made to identify the presence of unexploded ordnance following an air raid, often the damage and destruction caused by detonated bombs made observation of UXB entry holes impossible. The entry hole of an unexploded bomb can be as little as 20cm in diameter and was easily overlooked in certain ground conditions.

Incendiary Bombs>

Image showing a 1kg German Incendiary Bomb

Image showing a 1kg German Incendiary Bomb

Incendiary bombs (IBs) are air-delivered weapons designed to cause fire. During WWII, there were several variants utilised by the Luftwaffe – from the small 1kg IBs to large oil/phosphorous bombs.

In terms of the number of weapons dropped, small IBs were the most numerous. Hundreds of thousands of these were dropped throughout WWII. The 1kg variant was magnesium cased and filled with thermite.

They were dropped in containers, which would release the bombs at height, often distributing them over a wide area. When they failed to explode, they could easily go overlooked within debris/rubble, or in certain ground conditions.

Large incendiary bombs were often the same shape as HE bombs. However, they were thin-skinned and were not designed to penetrate the ground, but to split and spread their contents.

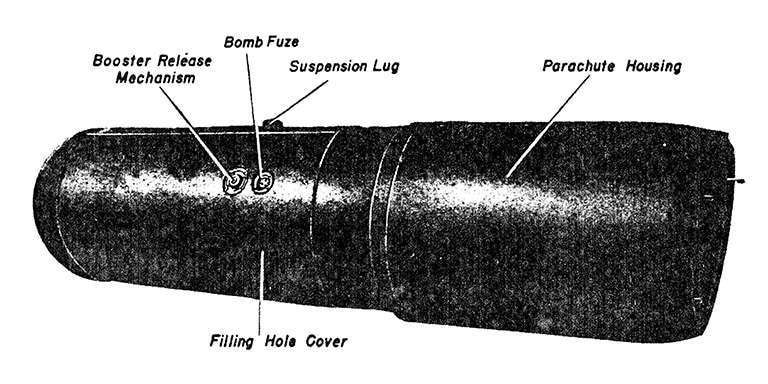

Parachute Mines>

Schematic diagram of a LMB Parachute Mine

Schematic diagram of a LMB Parachute Mine

Also referred to as ‘Aerial Mines’ or ‘Ground Mines’, German Parachute Mines were an adapted naval weapon which were deployed over land targets to act as large blast bombs. They were very large weapons, designed to have slow rate of descent on a parachute enclosed within the body of the device. They were first used against land targets in the UK in September 1940. The two main variants were the Luftmine A (LMA), weighing 500kg, and Luftmine B (LMB) totalling 1,000kg.

When these mines were utilised against targets at sea (their original purpose), they would sink to the bottom, and an anti-shipping detonator would activate. These were originally magnetic, but later both acoustic and magnetic/acoustic fuzes were used.

Whilst it would not be expected to commonly encounter these on land, they are frequently encountered in the marine environment, and should be considered during offshore works.

Read more about the services we provide to mitigate UXO risk

Explore our Case Studies

Frequently Asked Questions

Browse the most commonly asked UXO questions or contact us if you have a specific enquiry

UXB is the acronym for ‘Unexploded Bomb’ – usually an air-delivered weapon which failed to function as designed. UXO refers to any type of ‘Unexploded Ordnance’ – for example, it would include items of small arms ammunition, landmines etc. as well as UXBs.

UXO risk can vary considerably across the UK. In general, those areas which contained viable military / strategic targets were most at risk from bombing – major cities, industrial centres, docks, airfields, manufacturing sites etc. Some of the most densely bombed cities in the UK are listed below:

- UXO risk in Belfast

- UXO risk in Bath

- UXO risk in Birmingham

- UXO risk in Brighton

- UXO risk in Bristol

- UXO risk in Canterbury

- UXO risk in Cardiff

- UXO risk in Chelmsford

- UXO risk in Clydebank

- UXO risk in Coventry

- UXO risk in Dover

- UXO risk in Exeter

- UXO risk in Great Yarmouth

- UXO risk in Hull

- UXO risk in Liverpool

- UXO risk in London

- UXO risk in Manchester

- UXO risk in Newcastle

- UXO risk in Norwich

- UXO risk in Nottingham

- UXO risk in Plymouth

- UXO risk in Portsmouth

- UXO risk in Sheffield

- UXO risk in Southampton

- UXO risk in Swansea

- UXO risk in York

Current and former military land (airfields, ranges, training areas, munitions manufacturing and storage facilities etc.) can also often have a risk of UXO contamination.

Do not disturb it and get immediate assistance from the Police or from a commercial UXO risk mitigation company like ourselves.

Yes – many unexploded bombs do not penetrate straight into the ground, but more commonly conform to a ‘J-Curve’ – ending their trajectory at a lateral offset from point of entry. Some of the recent UXBs uncovered in London were found under buildings which pre-dated the war. It is thought that they fell into adjacent ‘bomb sites’ unnoticed and unrecorded.

Land Service Ammunition (LSA) and Small Arms Ammunition (SAA) are the most commonly encountered categories of UXO in the UK. LSA encompasses grenades, mortars, mines, rockets and projectiles. Of these, grenades, mortars and projectiles are the most commonplace, and are encountered with some frequency by members of the public and the construction industry – often on land historically used by the military. Unexploded German air-delivered bombs also pose a considerable risk in the UK, but are less common. Of the various types of German UXBs, the 50kg bomb was the most commonly dropped high explosive, and of the incendiary bombs – the small 1kg variant was the most widespread.

Items of UXO can contain unstable compounds which become more sensitive with age. UXO rarely becomes inert or loses effectiveness with time if it remains intact. However, buried UXO will not spontaneously explode if left alone. It would require some input of energy (heat, shock, vibration etc.) to initiate it.

This is highly unlikely if the item of UXO has been buried deep in the ground, and even for shallow-buried items or items laying on the surface – a change in the conditions surrounding the item of UXO is needed to cause it to detonate.

The depth that an air-delivered bomb can penetrate into the ground depends largely on the density of the underlying geological strata. In generic ‘London Clay’ the maximum bomb penetration depth (BPD) for a 500kg bomb can be around 12m below ground level. However, the velocity of a UXB can be retarded and sometimes stopped by strata such as dense gravels or a high rock head. 1st Line Defence can provide site specific assessments of maximum BPD based on borehole logs or during on-site support.

Possibly – however, each case and site is different. Finding a buried item like a WWII-era grenade or mortar may indicate that the area was utilised by the military historically, and that more might be present. If an unexploded air-delivered bomb was found in the area, it may demonstrate that during the war, ground conditions, frequency of access or levels of damage were such that evidence of a UXB entry hole was overlooked – and therefore that other such evidence could have gone unobserved.

Not necessarily. It is usually the case that the risk of UXO remaining will have been removed at the specific location of and down to the depth of post-war foundations and excavations. However, away from these areas, and at greater depths, the risk of UXO being present can remain. As an example, a 3m basement may have been excavated post-war. Down to this depth and in the area of the basement, the risk of UXO will have been removed. However, maximum bomb penetration depth can be up to 12m below ground level, so the risk of UXO remaining will not have been negated.

UXO is an acronym for the term ‘Unexploded Ordnance’, which is used to refer to bombs, projectiles, small arms ammunition etc. which may have been fired, dropped, launched or projected and should have exploded but failed to do so. The size or shape of any item of UXO does not indicate its potential danger. Small items of UXO can kill and maim if handled incorrectly.

Looking for a UXO risk mitigation company?

Contact us for more information, we are experts in our field and are here to help.